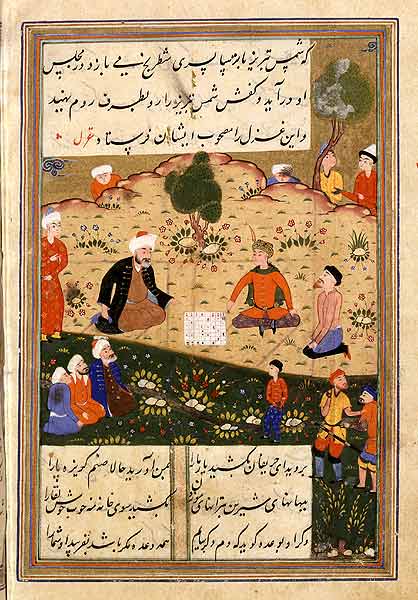

The contents are conversational and go from poetry to jokes to stories to chatter. The language is by turns playful and teasing, desperate and yearning, mystical and sensual. These weren’t poems written down on single scrolls to be framed in libraries, they were part of an effusive, rambling discourse and within the telling of a story Rumi might digress so often you wonder if he’ll ever finish the tale.

And they’re bursting with Sufi wisdom. Sufism is the happy place where a liberal mindset can relate to Islam beyond its rather severe appearance, it’s the playground behind it where one can groove with the whole whirling dervishes in long robes thing, the elegant architecture of the mosques, the mournful wail of the call to prayer like a call to attention, a reminder to be here now and say wow, what a wonderful world.

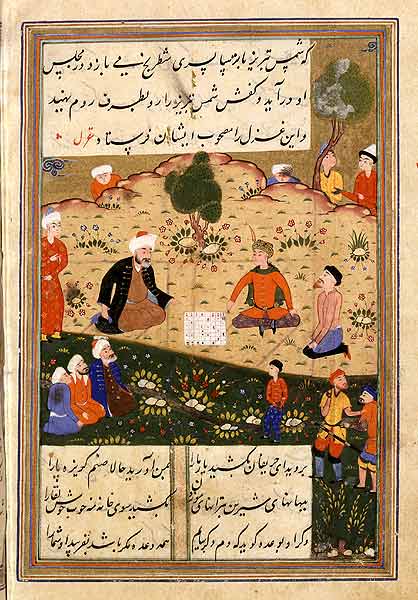

a 15th century edition of Rumi’s words

The poems of Rumi are accordingly marketed as ecstatic love poetry delighting in the whole tingling thrill of being enamoured with life, the universe and everything, a sense of bliss that transcends comparisons and divisions:

‘Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing, there is a field. I’ll meet you there. When the soul lies down in that grass, the world is too full to talk about.’

And therein lies the joy of Sufism, it’s religion that doesn’t prohibit or exclude, it doesn’t pin a list of commandments to the door of its tent, rather it’s open on all sides to anyone who hears the call.

But it’s not all feel-good poetry, there’s genuine heartbreak and longing when God doesn’t show up. there’s sleeplessness and bitterness and recriminations. Yet all the rancour and sorrow disappears once the presence of God, the Beloved, is felt again. As Rumi laughs in the self-aware story of Solomon and the Flies. The flies turn up to see Solomon the Just to make a case against the wind – they’re tired of it pushing them around all the time. Solomon, wise Solomon, calls in the wind to hear its side of the story- the wind duly arrives and the flies are gone. Case dismissed.

The beauty of Rumi’s words are when it gives us an insight, a state of mind or heart that really has travelled through the centuries from him to us, not so much an idea as a way of experiencing the world. One story has a man robbed and beaten up by thieves and after picking himself up he prays to God to give thanks for the bandits, declaring that they have reminded him of what he doesn’t want. We might not be able to live with such an open heart most of the time but we might perhaps aspire to.

Or how about the tale of the wandering dervish who comes across another Sufi mystic who is praying but mispronouncing the words. He takes it as his solemn duty to correct his brother who seems sincerely grateful for the intervention. Feeling pleased with himself for being so righteous, the first dervish continues his journey around the lake but then hears a voice, brother, how does it go again? Turning, he sees the other dervish walking across the water towards him…

These stories were, of course, never originally written to feature within mass-marketed poetry books but were part of an oral tradition, stories told by Sufis to gatherings of followers, sometimes pious, something poetic and sometimes downright bawdy as in the tale of a woman who observes her maid having a good time with the donkey in the stable. Drawn by the cries of ecstasy, she spies on the love-making and observes that the donkey has an enormous throbbing cock and the maid is in erotic convulsions such as the mistress of the house has never known.

The next day she sends the maid to town on a shopping errand and enters the stable herself, bends over and the donkey approaches her from behind but thrusts so deep inside her it ruptures something vital and she dies. The maid apparently had put some kind of sheath on the donkey’s cock to limit its penetration. The moral of the story? Don’t attempt advanced spiritual practices without the help of a guide or it might go terribly wrong. Not exactly the kind of parable you’d expect from an Islamic poet.

But the tastes and sensitivities of an audience 700 years in the future weren’t any of Rumi’s concern. Rumi’s poetry makes us laugh, opens our hearts, spins our minds and it speaks to us in a chatty vernacular that makes the poet seem like the kind of person you’d love to have a cup of tea with.

Or at least so he seems in the books put together by Coleman Barks.

Because the odd thing is that Barks doesn’t speak Persian – much less ancient Persian. Rumi had traditionally been translated by rather turgid Victorians and Barks relates how he was told by the poet, Robert Bly, ‘these poems need to be released from their cages’.

So really, we’re reading the works of Rumi as Barks imagines he would have written them had he been alive towards the end of the 20th century. Barks, himself, seems like the kind of joyful, free-spirited poet that you’d like to have a cup of tea with and says he renders the poems by going into a kind of trance, what he calls ‘the heart of the soul’. In his introductions he holds court with Shakespeare, Blake and T.S Eliot, Ram Dass and Michal Stipe. Though we’re reminded that he’s human and opinionated as anyone when he goes off on one about the 1998 impeachment proceedings of Bill Clinton, calling the lead prosecutor Ken Starr a ‘poor, pasty, sexless slug’ – most likely an accurate description but a little out of place in a book of mystic poetry.

Given that he is human, one has to wonder how much poetic licence Barks takes with the works of Rumi but at the same time, the authenticity might not matter all that much. What something actually is perhaps doesn’t matter so much as what we make of it. And our cosy notions of Sufism don’t generally line up with actual Sufism in the world where it still survives, as I found out in my travels.

Looking for Sufis

When I first went to India I met an American guy called Ali who became my mentor. He was a nuclear physicist working on the missile program in the 60’s in California until he took LSD and then ran away from America and ended up becoming a Muslim in Morocco under the tutelage of a Sufi master. He would go round to see his teacher each day and be given a spoon of majoun, a kind of edible hashish jam and then the evening’s teachings would begin. When he asked how he should make a living his teacher borrowed a sports car from somewhere, unheard of in Morocco at the time, and drove Ali around the main square a few times and dropped him off opposite the police station with a suitcase of hashish. Now walk home, he was told. It was about learning the art of invisibility, he concluded and a career as a smuggler began there.

Ali passed on to me insights that had been given to him by his teacher and I fancifully imagined I was part of a spiritual lineage. I’d recite lailahaillallah to myself in rough moments on acid trips, there is no god but god, nothing is real except this. I devoured the poetry of Rumi via Coleman Barks and became the annoying kind of person who had a Sufi story for every occasion, dispensing ancient wisdom wherever it was or wasn’t needed.

But still I was hungry to go to the source. So when I hitchhiked to India at the age of 20 I asked about Sufis wherever I went and when I came to Iran i was assured that yes, the Sufis were alive and well and could be found in the Kurdish mountains. I met a student whose father worked for a bus company going to the Kurdish mountains. Oddly enough his father, the bus driver, claimed to be a dervish himself. He showed me the scar on his waist to prove it. Apparently a sword had been thrust through his body there.

I arrived in Sanandaj and, as was par for the course in the most hospitable country in the world, I was taken in by a random family and they took it upon themselves to help me find Sufis. The grandmother of the family also professed to be a dervish and assured me that she, too, had a scar. I was taken to a ritual where a local Sufi teacher taught in Kurdish and they played ecstatic music singing and playing on the daf, a cylindrical drum which they threw in the air and caught in a clap of thunder. It was beautiful and yet I wanted more. So my hosts got hold of a video of the local Sufis doing their winter rituals – bear in mind this was in 1997, way before videos were made to be shared.

An old VHS cassette started running and I saw a video recorded on a home camera of a room of men and boys chanting Allah, Allah, Allah and while high on God, shoving swords through their waists. Some hammered spikes into their heads. One guy was even shot. And children were facing the camera with big smiles as they cut their tongues with glass. The kind of thing that would get 10 million views on Youtube now but back in 1997 was only for home consumption.

I didn’t remember Coleman Barks mentioning any of that.

I had come looking for the exotic, mystical Sufism of the books and found something much more authentic and unnerving. It occurred to me I was a spiritual tourist hunting for my bit of spiritual wisdom to take with me on my travels. There weren’t currently any weekend courses on Sufism for lost English hitchhikers and so I continued on my way.

Now I’m a good deal older and have learned to be a little less enthusiastic about solemnly retelling Sufi stories when friends are in a personal crisis of one sort or another but what’s the point of doing a podcast on Rumi if I don’t get to tell my favourite tales? I’ll keep it to two or three.

A few Sufi stories

It’s almost obligatory to begin with the guy (they’re all guys, this was the 13th century) who leaves his camel outside a mosque and goes into pray. He comes out all glowing with holiness and discovers his camel has gone. Fuck you, God, he yells, I trusted you! Then a passing dervish observes, yes, trust God but tie up your camel.

To be honest that one could just as well be an Aesop’s fable.

It gets more beautiful with the tale of the man whose will decreed that his inheritance should go to his laziest son. Rumi observes that mystics are experts in laziness. They rely on it,

Because they continuously see God working all around them.

So after the father dies, his lawyer asks the boys how they know a man; the first two sons say they know a man by the sound of his voice, just as one might tap a clay pot before buying it to see if there’s a crack. But the third son declares:

‘I know him from what I say,

And how I say it, because there’s a window open

Between us, mixing the night air of our beings.’

He’s evidently the laziest and wins.

But my favourite is probably that of the man who goes away somewhere exotic on a business trip and he asks everyone in his household, from his wife down to his pets, what they would like him to bring them back. His wife and children ask for various treats but when he gets to his songbird it simply asks him, when you get to your destination and you see my cousins singing in the trees, please tell them about how I live here in this cage.

The man says, are you sure that’s all you want?

That’s all.

The man is rather confused but keeps his promise and when his business is done, he finds some birds in the trees and relates the life of his songbird in its cage. A bird in the tree stiffens at this tale and falls down to the ground, stone dead.

The man is rather distraught and it’s with a heavy heart that, upon returning home, he tells his songbird what happened. But things get worse. The songbird hears the story, then it, too, stiffens and falls down to the bottom of the cage, dead. The man is now totally tripping out and he carries his songbird out to the garden whereupon…it springs back to life and flies to a branch of a tree. Freedom.

The man realises he’s been had. But tell me, he implores the bird, what was in the story that taught you that trick?

The bird replies: My cousin showed me that it was the beauty of my voice that kept me prisoner. All I had to do was surrender that and freedom would come my way.

Ah what the hell, one more.

2 teams of artists are given the job of preparing a beautiful space for the king. They’re each given a room separated by a curtain so they can’t see what the other side is up to. Both teams work furiously for a week and the king is invited to see the results. The first room is full of hanging lantens, fancy silks and rugs, sculptures and paintings. It’s gorgeous. It’s divine. The king can’t manage how a room could be made more beautiful. But then the curtain is pulled back and everyone’s breath is taken away. The second team of artists left their room empty but spent the entire work scrubbing and polishing the walls until they became perfectly reflective. The beauty and wonders of the first room are mirrored here in layer upon layer, multiplying the beauty beyond comprehension.

And this, Rumi suggests, is what we should do with our hearts – polishj them to reflect and honour the beauty of the world.

You can find my podcast, Telling Stories w/ Tom Thumb on Spotify, Apple or anywhere you listen to podcasts.