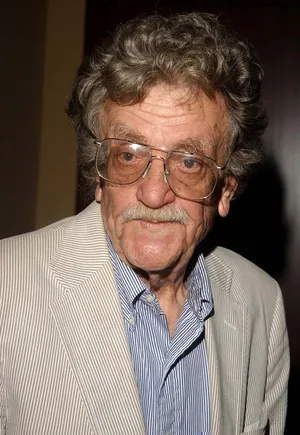

It sometimes happens in the world of arts that a musician, an actor, a writer achieve a certain status with the passing of time where their work is no longer regarded on its own merit but as the charming output of a beloved creator who, for al their foibles and flaws, can essentially do no wrong. Whatever criticisms their contemporaries might have had of them are blown away with the wind as each successive generation discovers them and eagerly joins their legion of fans.

Kurt Vonnegut is one of these. A struggling science fiction writer selling short stories to feed his family in the 50’s, he hit gold with his novel Slaughter-House 5 in 1969 and became, as the New York Times had it, ‘the counterculture’s novelist’. Funny and laconic, wacky and surreal, it was the kind of book you could read while you were stoned.

But it was also an anti-war novel which chimed with the mood of the times with anti-Vietnam protests going on. Slaughterhouse 5 was set in the second world war and in particular focused on the horrific fire bombing by the allies of Dresden which Vonnegut had experienced in person as a prisoner of war of the Germans, emerging from his underground shelter to find that much of the city had been burned down and 25,000 people were dead overnight. He was assigned the duty of uncovering bodies from the rubble, an exercise he would later, with his characteristic black wit, call ‘an elaborate Easter egg hunt;.

It might be that it needed a new generation to even contemplate that the Allies, who had fought such a crucial and moral war, could have done anything egregious, but Vonnegut wasn’t capable of writing a pure account of his traumatic experiences. While Slaughterhouse 5 was clear about the horrors and possibly the inevitabilities of war for a species as fallible as ours, the main character also jumped around in time, sometimes slurping syrup meant for pregnant woman as a prisoner of war in Germany, sometimes as a human exhibit in a zoo on the Planet Tramalfadore where he had been kidnapped and was put on display with a famous porn star.

As always with Vonnegut, pathos and bathos competed on the page. As jovial and jaunty as his written language was (the novel began with the line ‘all this happened, more or less’), an aura of cynicism and despair surrounds his stories, much like the old guy in the bar who can’t help but joke the whole day long but never really seems to laugh.

And yet Vonnegut was funny. And clever. He wasn’t a great writer by any standard. The characters in his books are paper thin, there’s little description, and what poetry in his writing that is to be found is of a haiku-like brevity, sometimes just the odd line that illuminates something dense with its simplicity.

“Of all the words of mice and men, the saddest are, “It might have been.”

“Everything was beautiful and nothing hurt.”

And his novels are full of little parables and stories that stick in the mind like a piece of liquorice on your teeth, hard to remove and yet you don’t entirely mind tasting it again with your tongue. You sense that he’s enjoying himself with the tales he tells and while he didn’t have the talent to write something like Animal Farm, he runs off little ironic sketches, often attributing them to a fictional writer called Kilgore Trout. One of Trout’s stories, for instance is called The Money Tree, which disproves the old maxim and actually does produce dollar bills as its leaves, with the result that humans come and fight over it, kill each other and their bodies serve as fertiliser for the tree to keep on growing.

Kilgore Trout, a thin veil for Vonnegut himself, outdid himself with his analysis of the Gospel story, where he has aliens come along and try to work out why humans are so helplessly mean to one another. The aliens read the Bible and decide that the central message is:

Before you kill somebody, make absolutely sure he isn’t well connected.

The flaw in the Christ stories, said the visitor from outer space, was that Christ, who didn’t look like much, was actually the Son of the Most Powerful Being in the Universe. Readers understood that, so, when they came to the crucifixion, they naturally thought…

Oh boy—they sure picked the wrong guy to lynch that time!’

I’m not aware of anyone else who, in the intervening 2000 years, has recognized this obvious subtext to the world’s most famous story. It took a middle-aged science fiction writer to call it out and it was this capacity that gave Vonnegut at times the truth-saying air of the child in the Emperor Has No Clothes.

As an aspiring writer, it was heartening for me to read Vonnegut because I could imagine myself writing stories like that. Anna Karenina, Crime and Punishment? I doubted I could ever produce anything of that stature but Cat’s Cradle which features a physicist who invented a substance that would instantaneously turn water into ice, inadvertently causing the world to freeze over, yes, that was within my capabilities. And yes, even I as a teenager, could sense that Vonnegut’s writing had never quite grown up and yet it had a defiant charm as a result. A kind of Peter Pan quality.

Vonnegut wrote several novels of varying quality which make for a light afternoon read but he was also capable of poignancy and insight, especially in regard to the injustice of the world. In Slaughterhouse 5, he wrote:

‘Every other nation has folk traditions of men who were poor but extremely wise and virtuous, and therefore more estimable than anyone with power and gold. No such tales are told by the American poor. They mock themselves and glorify their betters. The meanest eating or drinking establishment, owned by a man who is himself poor, is very likely to have a sign on its wall asking this cruel question: ‘if you’re so smart, why ain’t you rich?’ There will also be an American flag no larger than a child’s hand – glued to a lollipop stick and flying from the cash register.’

Vonnegut preached kindness at every turn but didn’t seem to find much of it in the world. The characters in his books were mostly unlikeable or helplessly flawed and though he will be remembered as the irascible grandfatherly cultural icon he came to be, a man who quipped that he should sue a cigarette company for failing to kill him though they had promised him to do so daily on their packets, he didn’t have much hope for humanity. Wise to the short term vision of the world he declared:

“If flying-saucer creatures or angels or whatever were to come here in a hundred years, say, and find us gone like the dinosaurs, what might be a good message for humanity to leave for them, maybe carved in great big letters on a Grand Canyon wall? Here is this old poop’s suggestion: WE PROBABLY COULD HAVE SAVED OURSELVES, BUT WERE TOO DAMNED LAZY TO TRY VERY HARD…AND TOO DAMNED CHEAP.”