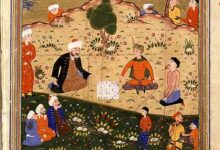

There was once a king who discovered that no sooner had he left his palace than his wife called down her lover, a black slave, from the tree where he was hiding and began an orgy in the royal courtyard as all her servants also copulated with the other slaves.

There was once a king who discovered that no sooner had he left his palace than his wife called down her lover, a black slave, from the tree where he was hiding and began an orgy in the royal courtyard as all her servants also copulated with the other slaves.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0I6UB8aL4V8

He had his wife executed and then proceeded to marry every fair lady in his kingdom, making sure to secure himself from the treachery of women by putting each to death the morning after the marriage.

So things went on until he married the daugher of his chief advisor, a girl named Shahrazad. After the marriage had been consummated, they lay back on the royal bed and, to pass the hours until her imminent death, Shahrazad began telling the king wondrous stories of love and destiny, of genies and mermaids, of gossipping barbers and scheming matchmakers – cutting short each tale just before dawn so that the king would let her live another night to hear the end of the story.

She continued thus until she had born the king 3 sons and he had quite lost his heart to her and, declaring a grand celebration and inviting the poor to all come and eat at the palace, the king renounced his vow to never trust women and quit his murderous ways.

The Nights are at once a treasure of Middle Eastern storytelling and an anthropological guide to the medieval Arabic world. There are men who fall violently in love at the mere description of a fair woman ‘like the moon at its fullest’, kings whose richness is measured in the number of eunuchs (castrated slaves) that guard their harim, and saintly souls who cast no blame upon their persecutors, attributing all that happens to the divine will of Allah.

While familiar stories like Al-a-din (Aladdin), Ali Baba and the 40 Thieves, and Sinbad the Sailor weren’t in the original Nights from the 10th century, they are part of the Middle Eastern storytelling tradition and so have squeezed their way into the modern versions of 1001 Nights – and, arguably, deserve their place for the richness of their fantasy and twisting plots.

1001 Nights (sometimes called 1000 Nights and a Night) drew on old Persian stories, Indian tales from the Panchatantra and elements from Egyptian folklore, all diffused with the spirit of Arabic storytelling, pandering to the prejudices and beliefs of the age. Much of the references would be lost upon a modern audience unless they read the translations from Richard Burton, a remarkable traveler and anthropologist whose footnotes to the Nights are often more entertaining than the stories themselves. When, for instance, a old matchmaker returns with a sad face after a young man has sent her to represent his love to a girl he saw briefly on a 3rd floor balcony, Burton notes that her expression is but a ploy ‘the usual pander-dodge to get more money’.

At times, reading 1001 Arabian Nights needs a tolerance for attitudes which are quite strange and despicable to a modern audience. When the queen (whose adulterous behaviour initiates the whole story) summons her lover, we learn that:

‘the Queen, who was left alone, presently cried out in a loud voice, “Here to me, O my lord Saeed!” and then sprang with a drop leap from one of the trees a big slobbering blackamoor with rolling eyes which showed the whites, a truly hideous sight.7 He walked boldly up to her and threw his arms round her neck while she embraced him as warmly; then he bussed her and winding his legs round hers, as a button loop clasps a button, he threw her and enjoyed her.’

It was these kinds of sexual passages that made such an impression on Victorian society and which are still omitted in many modern retellings of 1001 Nights. Love translates as little more than sexual desire and great emphasis is placed on the desired purity of virgins as well as the trickiness of both of the sexes when it comes to their illicit affairs.

And if there is anything more important than sexual desire in the Nights, it could only be material desire. Nothing excites the passions of the protagonists more than the prospect of material wealth, all longing to possess marble palaces and white slaves and eunuchs galore! With each wedding we hear of the 7 fine dresses in which the bride is presented, dripping with jewels and fair cloth, gratitude is expressed with fine gifts and there are countless tales of treasures to be found at the risk of losing one’s life to malevolent jinni or giant birds.

Some have suggested that these tales of fancy and wonder make sense when one considers the poverty of the traditional audience to the stories of 1001 Nights, but how different is the modern obsession with the prospect of winning the lottery?

In short, though the style of the Nights makes them inaccessible to many, there are stories there which shed light on the caprices of human behaviour, shine a light on an age long passed and make modern storytelling seem rather simplistic – there are tales within tales within tales until you’re no longer sure who is really narrating or what the meaning of the story is – if such a thing is ever to be grasped at all.

1001 Nights, from whichever angle you approach it, is somewhat like an Arabic suq, a labyrinth of side streets that always take you somewhere, even if it’s not where you thought you would be going.