I remember the confusion I felt in my religious studies class at school when the teacher asked me what Zen was.

“I don’t know, sir.” I shrugged.

“Correct!” I was told. Mr Hickman, if you’re reading this, thank you for the introduction to Zen.

By its very nature anything written about Zen is absurd. That didn’t stop the like of D.T Suzuki and Alan Watts from writing very eloquently on the topic but ultimately you either get it or you don’t – and in the moment you do get it you’ve probably lost it again anyway.

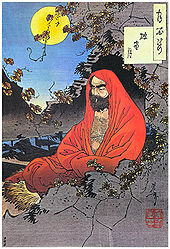

The following story of Bodhidharma, an Indian monk accredited with bringing Zen Buddhism to China where it flourished, might help illustrate the point.

The Emperor of China at the time was a proud supporter of Buddhism and had paid for many new temples to be built, scrolls to be written and provided for a large number of monks that the virtue of The Way might bring peace and harmony to the kingdom.

The Emperor of China at the time was a proud supporter of Buddhism and had paid for many new temples to be built, scrolls to be written and provided for a large number of monks that the virtue of The Way might bring peace and harmony to the kingdom.

So when news reached him of a wandering monk from India he was anxious to meet the stranger from the homeland of the Buddhist faith. Bodhidharma walked into the palace and stood before the monarch who then asked him:

“Behold, I have built temples, furnished libraries of Buddhist texts, sustained communities of monks! What then is my merit?”

“None whatsoever.” Bodhidharma replied.

A little flustered, the Emperor made a show of humility and asked:

“Well, then, perhaps you would care to enlighten me as to the teachings of the Way?”

“There is no Way.’ Bodhidharma told him.

“Who the hell are you?” the Emperor demanded to know.

“I have no idea.” And with that, Bodhidharma turned around and walked out of the palace.

Zen did take a hold despite its essence being as elusive as air and to this day there are plenty of Zen temples in China and Japan where monks wake at 4am, maintain the gardens and meditate their entire lives on unsolvable koans – riddles such as who were you before you were born?

The famous Zen practices of staring at walls, trying to work out the sound of one hand clapping and the sudden, unexpected slaps around the head a gardener – who usually turn out to actually the Master – are all meant to bring about the shattering of one’s habitual identity and consciousness to allow the Buddha-Self inside, our true nature, to emerge.

I have my doubts whether that ever actually happens to anyone but the quality of Zen seems to me self-evident. Living is in itself so arbitrary – why here and not there? Why now and not then? Why be born to these parents, to this gender, why to make the particular decisions that we do in an ocean of choices? So Zen represents for me everything else that we are not but which gives us meaning.

In this sense it comes very close to Taoism which reminds us that the window is not the frame but the space we look through, the space that was always there. A cup is made of clay but it’s the emptiness inside that makes it useful.

Moreover to Zen there’s a nowness that gives the tradition such vitality. Our plans for the future, our hopes, our dreams all evaporate in the wind of Zen. It also makes a mockery of our opinions, our preferences, our taste. Take this Zen story:

A man goes to the butcher and asks:

“I’m having a party tonight so give me your best cut of meat.”

The butcher just shrugs. “These are all my best cuts of meat.”

600 words into this article and you’re probably agreeing that it’s ridiculous to write about Zen or at least for me to write about it and you’re absolutely right. As my religious studies teacher first taught me, I have no idea what it is.

But as a rather illuminated person once asked me:

“Who is it that wants to know anyway?”

Which seemed to me like the ultimate Zen koan.

Who are we?