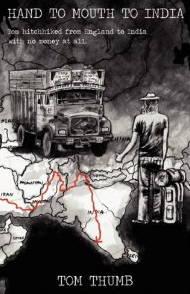

Hand to Mouth to India

I wrote Hand to Mouth to India while sleeping on the beach in the winter of 97/98 and it’s the tale of how I hitchhiked from England to India with no money.

It’s the most successful of my books and every now and then I get an email from some 20 year old guy who has just come across it and they tell me how it’s inspired them to hit the road and hitchhike to Patagonia. Get travel insurance, I tell them, stay in touch with your folks…

You can read the first 3 chapters here or if you want to download the whole book as a PDF in your inbox just subscribe here below :)

You can also order Hand to Mouth to India in print or on the Kindle.

Preface to the Third Edition

It’s been over ten years since the first photocopied manuscript of Hand to Mouth to India came to the light and the cocky 20 year old who decided a thumb was all he needed to see the world becomes more and more a stranger to me. There were times when I couldn’t even look at the book for the youthful arrogance and the overexcited passages about Sufism.

This isn’t me, you understand, I told readers before lending them a copy, I was just a kid back then…

Only when I’d put enough time between me and the youthful author was I able to feel less threatened and even look back with some tenderness on this precocious and vulnerable rebel.

This isn’t me, you understand, but it’s charming in its own way…

This is the third edition, which sounds good and I thought I’d give a quick summary of the adventures surrounding the book. After arriving in Goa in December 1997, I spent a season sleeping on the beach, surviving mainly on the charity of friends and locals. The freak who had inspired me to make the crazy trip in the first place bought me pens and paper so I could write the book and Nepalese workers at the local bakery gave me bread rolls and glasses of water while I wrote my 2000 words a day.

The real thanks though goes to the local fruit lady whose vicious machete dissuaded a cow from eating the manuscript one afternoon while I was drinking a coconut.

I typed the book up on a friend’s computer and then, to save me money, he had it printed out in size 7 font so that the entire 90,000 word book was condensed onto 40 pieces of A4 paper. By making photocopies of these I was able to survive the monsoon in the Himalayas and help countless backpackers lose their sight as they squinted at the tiny typeface.

When winter kicked in, I returned south to Goa and borrowed some money to print up 500 copies of Hand to Mouth to India with a nice little hand-drawn cover. For the next month I broke all the rules, selling the copies wherever I went – in cafes, on the beach, in the middle of trance parties, even in the jungle at midnight.

I sold a couple of hundred copies, enough for me to escape India and I flew to Turkey where I hitchhiked to Syria, 70 books stuffed into my rucksack. I got fever along the way and had to beg the help of the drivers to lift my bag up into their trucks. The road took me down through Jordan to Israel and my entry into the Israeli immigration hall was marked by my Indian-made rucksack splitting down the seams and spilling piles of my travelogue all over the floor. Israel security ended up checking every single page of every single book.

A chance encounter in a head shop in Portobello Road, London, convinced the owner to publish the book for real and in July 2000, Hand to Mouth to India entered the consciousness of the first world. With a beautiful new cover and patchy media exposure, Tom Thumb got reviewed, interviewed and generally made fun of. What’s this privileged First World kid doing begging food from poor people?

The book didn’t make any money but it sold 1500 copies and ever since I receive a few emails a year from people who have bought, borrowed or stolen the book, reminding me the journey hasn’t been entirely forgotten.

Hand to Mouth to India

“The man who sleeps on the floor will never fall out of bed”

(Old Turkish proverb)

Chapter 1

Freewheeling (England, France, Luxembourg)

I walked out one midsummer’s morning to hitchhike to India with no money at all. I had with me my clarinet, a sleeping bag, a ticket for the boat to France and a couple of loaves of date bread so as to be sure of not starving to death within the first day or two. I paused beneath a giant billboard poster of Tony Blair smooching the street with his smarmy, sinister smile and then walked on to exchange grey cities for palm tree beaches, politicians for snake charmers. A stranger in my hometown, I walked down to the coastal road with little but my freedom on my back.

Already a memory were the touching farewells of heartfelt friends and bosom buddies I never knew I had, who had sprung out into my path around town to suffocate me in tight emotional embraces. Not many thought I’d get very far, or even survive and with tearful reluctance they crossed me off their Christmas card lists.

But all camaraderie dies when you hit the road alone and prepare for the vessels of Fate to bear down upon you in screeching metal boxes on wheels. Standing as an exposed and anonymous figure with an aching thumb, it’s an old journeying adage that there’s a fine line between hitchhiking and waiting by the side of the road like an idiot.

My first lift pulled up within minutes and I jumped in without a glance back.

“I’m going to India!” I told the driver smugly, as I strapped on my seat-belt.

“Well, I can take you as far as the university.” he told me doubtfully.

A couple of rides later, I was sitting on the pebbles of Hastings Beach, munching my date bread and wishing I could afford some chips. The sea was smothered in a miserable gloom and refused to yield any hint of what might lie ahead. But during the previous winter in Goa, I had sat at the feet of various hobo gurus and learnt that if you have eaten this day then you are successful. Period. Providence had already provided well for me in a penniless tour of springtime Europe. But fear has the habit of mushrooming back up at even the thought of rain and so I flicked open the pages of Kahil Gibran’s “The Prophet”, to seek some confirmation. I read:

“Is not the fear of being thirsty when your well is full, the very thirst that is unquenchable? And what is fear of need but need itself?”

Things were going to be fine. More or less. I threw a stone at the moody waves and turned to stomp back to the road, large and weighty doors of the past slamming shut behind me.

Towards the end of daylight, I arrived at Dover, having survived some fairly uninspiring conversations. I found at the dregs of Britain’s roadways, a skaggle of hitchhikers attempting to leave this tiny island and rejoin the greater potential of the Continent. We were all experts at travelling light but their long faces told me that no one was getting any luck. I caught the boat and made my bed on the tiled floor of Calais port, pretty much at the feet of the other people waiting on the plastic seats. I was quite content though-sleeping inside is always a bonus in this mode of travel, even when it is punctuated with loudspeaker announcements every ten minutes for the departing ferries.

Some hours later, I dragged myself out of the feverish horrors of half-sleep and heaved my bleary body out into the chilly morning to make an early start and avoid competition. Outside, I discovered that the same notion had occurred to all the other hitchhikers. We threw etiquette out of the window and all tried to flag down truck drivers with no sense of order or queuing-the equivalent of cutting each other up when driving. Hitchhiking is hardly a communal activity. Unless an exceptionally beautiful girl is present no group larger than two is going to get any lifts. So the sight of another hitchhiker is rarely a welcome sight.

There seemed to be no real chance of moving out with so many people waiting, so I chose to walk a few miles in search of a better spot, leaving behind a die-hard French couple who told me:

“We’ll sleep here if we have to-we don’t care!” They were off to India in the autumn and we speculated that we might meet again in more serene surroundings than this murky slip road. Wishing them luck, I sweated my way up the road and caught a chance lift with an Englishman, winging his way out of town after a croissant and a cafe.

Relieved not to be forced into my inadequate French, I set to navigating our way out of the confusion of roundabouts, whilst sizing up my benefactor of the hour out of the corner of my eye. He was a fat and bearded Geordie, called Jeff. He wore the image of an itinerant cowboy who swaggered into the saloons of every town with his guitar on his back; a rolling stone entertainer, paving his way through the towns of Europe. He had been a professional busker for the best part of ten years and within minutes, we were exchanging stories and anecdotes of playing music on the street-his far more rich and prolific than mine and so I let him do most of the talking, whilst I concentrated on a map of North-West France.

“Some days luck is with you and other days it’s not-simple as that.” He told me, “I was playing in a duo on the trams in Switzerland last year and me and my partner, Mike, we were playing an amazing set-all of our solos were bang on time, we were making up hilarious verses and we improvised a completely new finale. Then Mike went around the tram to collect money in his hat. And I watched him as he set off all confident like and slowly, he became more and more depressed until he came back with the lowest face you ever saw-no one gave us a single coin.” Jeff stroked his beard in remembrance. “But then a week or two later, we were playing together again on the trams and we were both really hung over, I forgot the chords to the song we were playing and two of Mike’s strings snapped-and before we could even attempt to finish, people were coming over and stuffing our hat full with all they had in their wallets.”

We avoided the exorbitant peage toll highways and hunted for the ‘A’ roads that ran almost parallel in elegant straight lines that rose and dipped over graceful hills through the countryside. The road intersected every small town on the route and every half an hour another village appeared on the horizon. Each settlement was heralded by a lonely white church, each with its own particular character and beauty.

With haystacked meadows and grazing sheep, I couldn’t have wished for a more picturesque route. Back on the road again I felt like I was on the first chapter of a book that promised to be a very good read.

Unhappily enough, Jeff turned out to be a Born-again Christian, though thankfully not of the evangelical ‘now listen up’ variety. He limited his sermon to a brief warning about the risks of Eastern wisdom:

“You see, many of the Eastern religions talk about making the mind empty-but that’s actually very dangerous!” And he’d pause to make sure I’d understood, “Because when the mind is empty, evil spirits can come in and start to take control!” Jeff was a good guy though and we settled down into a trusting repartee where neither of us needed to say too much.

We drove all day and came to rest in a small town with a pleasant, drifting river that carried bubbles and pieces of straw along no faster than need be. Jeff went off into town on the pretext of changing money, whilst I sat on the soft grass and played provincial blues on my harmonica. He came strolling back an hour and a half later with a happy, drunken swagger and we spoke wistfully about the strangeness of existence; two misfits sitting with their legs dangling over the riverbank, staring into the folds of twilight that closed the day about us.

My German army sleeping bag and waterproof poncho proved effective against the cold, dew and damp that are ever present in Northern Europe, even at the height of summer, whilst Jeff also struggled for comfort in the back of his van. Cold and wet nights are what I fear the most on the road. On the advice of my acupuncturist i carried a piece of ginger in my pocket as a remedy against dampness, an ‘evil chi’, the Chinese say. Then again, he also reckoned that diarrhea could be cured by filling the belly button with salt and waving a lit cigarette closely over it.

The next morning, we got ourselves together to pull out of town only to break down after two miles. Cursing, Jeff went off in search of a telephone but it began to rain before he’d gone a hundred metres. I sat patiently in the car, wondering if that was his karma for not sharing his beer session with me the night before. I looked to the drops of rain rolling down the windscreen for an answer. What the fuck am I doing here? I asked myself, as I do twenty times a day on the road. I just reclined the seat a bit and let the patter of falling water call the shots; strangely pleasant to be in some stranger’s car near a little red dot on the map.

With the help of some local mechanics, we got moving again and by mid-afternoon came rolling into Luxembourg City, where Jeff proposed that we raise some funds with his music in the public squares. He was looking for a gold-mine where he could work for a week or two and then use the earnings to chill on a beach in Portugal. And man, was this the right place! We struggled to find what name to call the people of Luxembourg-the Luxemese? The Luxish? The answer became rapidly clear-the Luxurious. For everywhere we looked were lush BMW’s and Mercedes cruising around in the nonchalant manner of the very rich. This tiny country measuring about 60 miles long by 50 miles wide lies as a select watering hole for the wealthy hippos of Europe. Jeff licked his lips in anticipation.

In addition, Luxembourg receives massive amounts of tourism from holidaying Europeans and Americans, whose guidebooks show them how to survive on $300 a day. they’re specifically recommended to take advantage of the authentic local cuisine of tacos and re-fried beans in the traditional grandeur of the main square where a large brass orchestra played Abba tunes twice a day.

There was no shortage of street performers, either, as fire jugglers, New York break dancers, concert flute players and didgeridoo dudes, all competed to empty the bulging purses of the visitors who clearly had more than they knew what to do with.

Jeff swaggered down to the Square in his cowboy hat and leather boots and began to set up his backing equipment and electric guitar. This was to be the first time that I saw busking being really profitable; I had busted my ass howling 1930’s Mississippi Blues on the streets of France and Austria, desperately trying to make some impression on an indifferent public. But then few artists are appreciated in their lifetimes… At least that was my conclusion on the days when I didn’t earn enough to even buy a cup of coffee, let alone a pint of whiskey.

Playing music on the street is great when things are going well. You can feel yourself bringing life and vitality to the city; a colourful bard of the urban scene, you can laugh and joke with the locals in true minstrel style. But on a bad day the street becomes the most heartless place in the world; the police move you on with unnecessary aggression, passers-by seem almost offended that you dare to break the monotony and when the few coins in your hat (as ‘bait’ to lure further additions) sit as lonely as only metal money can be.

On those dire occasions, you feel like laying down in the gutter and allowing the tarmac to swallow you up for all that anyone would care. Performing is a creation that must be resurrected every time you start anew. The maestro act of yesterday means little in the bleak and hungover face of the new morning. Jeff shared this feeling as he admitted to me that:

“Sometimes I push myself too far-playing every day without enough breaks. Then all the fun goes out of it and I become kinda drained and depressed. And I have to say to myself ‘Hey, Jeff! Take it easy, will you?'” It was for this reason that I’d grown tired of busking and was now giving it a rest.

Jeff had his routine pretty well worked out, sounding quite professional with his electric guitar and formulaic backing tapes. These laid down the percussion and bass lines for the five or six songs from which he never varied. His sparrow-like Geordie voice vanished when he sang, to be replaced by the clichéd American twang that can be heard in most modern music. His vocals were clear and bold though and the overall sound could be heard from fifty feet away, extending our target audience.

The arrangement was that he played opposite the cafe terraces to win the favour of the well-dressed businessmen and families who dined on pasta and wine. Between songs he kept up his spirits with the well-practised comments of ‘Thank you for that wonderful round of indifference’ or ‘No dancing on the tables!’

My job was to do the ‘bottle’, a name deriving, Jeff claimed, from the original Punch n’ Judy shows. A pretty girl used to hit up the crowds after the act, collecting the money in a glass bottle that contained a fly-the trick being that if she took her thumb off the top for too long, the fly would escape and then the puppeteers would know that she’d been trying to siphon the money for herself.

After about three or four songs, Jeff would give me the nod and I’d go into full hustle mode. I walked from table to table, shaking the hat to give the coins an expectant jingle and accosted the punters in the middle of their meals, persuading them to dip their soup-stained fingers in their wallets, as I cried out:

“Un peu d’argent pour les musiciens, s’il vous plait! Ein bischen geld, bitte, mein herr? Spare a bit of cash for the music, mate, so that we can eat?” Depending on what tongue was appropriate in this conflux of linguistic drifts.

With a bit of coaching from Jeff, I soon learned the various tricks to bring in more money: no one could be hurried into bringing out their purses. It was far more effective to introduce the idea to them slowly by mulling about in a relaxed saunter, to give everyone the idea that they were supposed to contribute. The first point of attack was always the table that gave most applause. From there I’d plan the rest of my route to gain the maximum possible attention. As long as I was loud and funny, polite and insincere, the hat I carried gained in weight rapidly and I couldn’t pretend we were so poor any more. We moved from terrace to terrace, Jeff playing the same set each time to the new cafe crew and, by the end of the evening, we’d got about $100 together.

As I was pretty inexperienced at plying the ‘bottle’, Jeff proposed that I take 25% of the take. I reckoned I was doing more than okay at the job but didn’t press the point as, after all, I was hardly trying to swell my pension funds. So I took an easy-come easy-go attitude about it and just got into the fun of new experience. That’s why I came on the road in the first place.

At the last cafe of our evening’s tour, a bunch of Brazilian businessmen implored us to share a drink with them. Beer always tastes good after hard work and it was only after the first sip that we looked up and realised that we were sitting with a group of sallow-faced, shifty-looking men. With the sly vibes of reptilian schoolboys, they wisecracked and competed for status amongst themselves.

“These men are all very rich men!” Our translator told us in a reverent tone. Looking from each screwed-up face to the next and, studying each pair of troubled eyes behind a worried mist of alcohol, it was clear that these were also very unhappy men. Maybe they weren’t praying hard enough to the Greenback Dollar God who promises to bring everlasting delight to his most successful devotees.

Below where we’d parked the van was a deep valley where a public park lay. I trotted down to find a shady place to sleep away from the main path and the harsh glare of the streetlights. Under the scrutiny of the many CCTV cameras that dotted the park, I tried to look like a casual late-night stroller, arm-in-arm with my sweetheart-sleeping-bag. But was there really anyone watching on the other end who gave a damn? No one came along to evict me but I spent an uncomfortable night being frequently awoken by the drunken antics of late-night clubbers, on the path some 20 metres away.

The morning didn’t start off too well. A persistent itch alerted me to the sadly undeniable fact that I was now host to invisible park fleas-‘What to do?’ as they say in India with a fatalistic waggle of the head. Then I managed to get into a full yelling row with the Dutch woman who ran the public toilets. She took exception to me washing my armpits in the sink and I only just about managed to clean up in a petty struggle of power, – the old hag kept turning off the water for a minute or so to demonstrate her authority, whilst I bent under the taps trying to salvage enough of the leftover drips.

As I left, a guy looking like a security guard passed me on the steps. I counted it as a close escape and went off in search of some breakfast with jingling francs in my pocket as a result of the previous night’s endeavours.

I stood in the supermarket, staring bleakly at the prices of fruit per kilo to see what I could afford-and so hapless did I look, that a middle-aged lady stopped and asked me in concerned German:

“Do you have enough money to eat?” And before I could effectively protest she handed me 200 francs (about $10) with the apology that it was not much and departed before I could find the appropriate words in her language to express my gratitude.

Kindness is like water and will find you no matter how low you stand. Even here in the heartland of capitalist Europe, there were angels who took my well-being upon themselves. Travelling hand-to-mouth restored my faith in the essential goodness of human nature. Frequently my hardened cynicism was left agape at the care and warmth that was almost always given to me when I was in real need.

I was getting hungry for the road again but Jeff persuaded me to stay and work for another night so that my journey would be better greased by my share of the evening’s take. We relieved the tourists of their spending money again and I became heartily sick of hearing the same poppy tunes of which Jeff never seemed to tire:

“And your smile, is just a big disguise, For now, as you realise, There aint no way to hide those lying eyes!”

Sleeping in the park was even worse that night, as party-goers stumbled upon my resting-place no less than three times. They were more freaked out than I though and I called out good-day to them in German and French from my reclining position in their path of reckless exuberance.

“Aaaargh! Un habite!” (‘a dweller!’) One of them called out in alarm and distaste, that there could be such people who slept out under bushes and trees.

My mood was greatly improved in the morning by the ridiculous bouncing form of a young American guy. He came scampering and bounding through the park and accosted me:

“Could you take a picture of me please?” Placing the camera in my hand before I could respond. He then darted away to pose by trees and hillocks with both arms splayed open wide. I particularly liked the surety with which he assumed everyone that he approached would be able to speak fluent English-well, these people are educated, aren’t they?

Despite our differences in character, I’d gotten along well with my road-buddy, Jeff-he was a good sort and a seasoned freak in his own right, bravely making his way on the fringes of society. I gave him my European map book, ripping out the pages I’d need and gathered the $50 or so that I’d made from the bottle. Small coins and shrapnel galore, the bane of all buskers, I managed to get them changed up into higher denominations before Jeff gave me a starting lift to a petrol pump on the edge of town.

It’s always useful to get dropped off at gas stations as then you can take hitchhiking onto the offensive, by hitting up the drivers as they stand around with petrol hoses in their hands, nervously watching the display rack up the litres and escalating cost. In this scenario, you get the chance to approach them personally and make a verbal contact that they can’t just ignore – some humanity is injected into the relationship between hitcher and driver, a warmth that is somehow lost when separated by a windscreen and a projectile speed of 8okmph, their rejection exhaust smoke leaving you coughing and black in the face. The personal approach also gives them the chance to see that you’re probably not a crazed axe murderer. Once they realise that you’re not a threat it becomes a lot harder for them to say ‘no’.

In some ways, though, I prefer the romance of standing by the side of the road, inviting the pot-shots of chance to sweep me away from my lonely mooring, my fate out of my hands. Also, the grace of the slowing car tends to produce more charming encounters, as these drivers are those who voluntarily have an affection for the free travelling spirit and make for much better company.

But if you want to get anywhere fast, then it’s best to be as pushy and bold as can be, soliciting every driver you can with cheerful and courteous turn of speech so that they consent before they have time to even think about it. The downside is that when very few drivers are actually going your way, you end up with a lot of polite rejections that really tax your energy and enthusiasm. This was one of those occasions and I became increasingly dejected and desperate. Walking in the mid-day heat amongst the intoxicating petrol fumes, I ended up weaving around like an alcoholic fresh in from the desert.

I was trying in vain to decipher the destinations of the cars by the tell-tale initials on their number plates, when I overheard an approaching couple of businessmen talking in cockney English. I approached them in my salt-of-the-earth accent and asked: “Excuse me, mate-you wouldn’t happen to be going towards Saarbrucken, at all, would you?” With brilled blonde hair, one of them gave a sneering laugh and replied:

“Nah, mate! We’re going to work !”

The implications were pretty clear and I was only consoled by remembering the story an old college tutor of mine had told me: he’d decided to hitchhike back from a conference he’d attended that weekend and had been waiting for a couple of hours in a lay-by when a van stopped. He ran quickly up and a head popped out of the window:

“Do you want a job?” The driver asked him.

“No!” he replied, with all the pride of a professional man, wondering where this was leading.

“Thought so!” came the retort and the driver sped off with a triumphant cackle.

Chapter 2

Round the Bend to Vienna (Germany, Austria)

I eventually got my rides into Germany and slept through each of them. I often get picked up by people who need someone to talk to so that they don’t doze off at the wheel, or else just to break up the monotony of pursuing the ugly concrete motorway. It doesn’t generally go down too well when the stray wanderer they’ve picked up passes out within minutes in the front seat, snoring loudly. But sometimes there are just no two ways about it. The rocking lull of each car’s motion pulled my eyelids inexorably together. On the road you need every bit of shut-eye that comes your way.

I got stuck again at a petrol station inside Germany and ended up approaching a tall, bald guy in my best German as he rummaged in the boot of his car. He responded in perfect English. He didn’t believe me when I told him my destination was India but he relented and let me in, allowing me the satisfaction of proof when I flashed the Iranian and Pakistani visa pages of my passport at him.

“Wow, man! You’ve got a long journey ahead of you!” Too true.

This turned out to be one of the best rides of my hitchhiking career so far. He was a large and lanky guy called Jan and he drove his Mercedes at a silent 200 kmph down the no-speed-limit German autobahn. The transformation of setting is one of the reasons I love this mode of travel. Five minutes earlier I was choking on the fumes and frustration of petrol pumps going nowhere fast. Now I was riding down the highway in style, a new friend to talk to at the wheel. Feeling groovy.

I learnt that Jan was something of a hi-tech prophet of the first order; a designer of future state-of-the-art computers, he was working on contracts with very wealthy German businesses and Austrian banks and it was clear that some serious money was involved.

Once he sensed that i was also a little eccentric he began to outline his whole project, growing in enthusiasm and eloquence as he went on; Jan was becoming the architect of computers that would possess souls-giving independent life to the byte-biting hardware recently formed into one being with the generation of the internet. This visionary who sat beside me with one hand on the wheel and both eyes trailing off into a grandiose distance, foresaw a near future when computers would be endowed with belief systems and values. He stood at the threshold of a revolutionary New Age that smacked of scary Bladerunner scenarios.

It was not all easy street for his notions, however, as he had to do daily battle with the dinosaur-like minds of the directors and ‘experts’ of the companies who hired him but were as yet too cautious to let him take the full reins of progress between his gnashing teeth. He ran himself blue in the face attempting to persuade these fat cats that computers would soon become something astronomically more than fancy calculators keeping score on the stock markets and providing space invader games for their kids.

Not only this but Jan was keenly aware of the potential dangers of computers gaining partial or full autonomy and considered that the whole process would have to be handled with the utmost care and aforethought. He considered that there were many malevolent influences who sought to contaminate or dominate this amazing potential for power in the forthcoming computer epoch. In this sense, he saw himself as a figure of light engaged in a struggle for good against evil. Already he and his like-minded associates were taking steps to forestall the dastardly, Lex Lutherish designs of the more sinister players in this particular game.

I began to spin off this warped conversational tack with relish and speculated on how the megalithic oppression of the multinational companies might be left behind as toppling giants with their minds stuck in the past, anarchic computer programmers rewriting the System from within. Soon at the top of the innovation and logistics departments of multi-billion dollar firms would be weird and warped techno-prophet minds right at the heart of the beast.

“Now you might laugh, Tom but I envision the whole drive towards advanced computer technology as mankind’s instinctive and unconscious flight from the hazards of the physical world-where we as humans are threatened by climatic, ecological and social chaos. So we’re perhaps retreating towards the internal kingdoms of cyber-space.

“And there will be infinite realms of wonder, magic and beauty-places where we can write the laws of physics ourselves and where the only limits to the nature of existence will be our imaginations. Once we learn how to fully connect the neural pathways of the human brain to silicon routes in. cyber-valleys, we can actually fully invest our consciousness into the machine!”

Right! Then we could truly liberate ourselves from the chains of individuality, merging minds with internet telepathy, possible once all cerebral constructs become compatible.

“So what do you think of the weirdos you met on the German autobahn, Tom?” Jan asked me with a wry smile, bringing my wandering mind back down to Earth for a minute. I laughed as I realised that as usual, I had been swept away with the force of another person’s passion and dreams. Reality on holiday. But really, what would Buddha have said at the prospect of such a vision? Perhaps this was an example of the other realms of heaven and hell that the Tibetan Buddhists are always talking about-and surely we’re meant to achieve enlightenment in this physical world, no?

I sensed, however, that these doubts were probably symptomatic of a mind that would be left behind in the next era and that my future children would have no difficulty in assimilating the cyber-dimension at all. Would I really come to lose the love and support of my offspring to a cortical shunt plug in the side of their heads? It couldn’t be, could it? If someone went back 100 years and told the people of that time that in the future you could talk to a special kind of box called a computer – he’d have been sent away to the loony bin or burnt at the stake. Jan confirmed my reasoning by reminding me that before the future is born, it is conceived in the minds of the dreamers who float above the reality of their times and plot a course to the islands of the impossible.

Back in the three-dimensional world, it turned out that Jan would be driving to Vienna the next day and as the sky began to grow dark, he offered to give me a bed for the night at his house in Stuttgart. It was what I’d been hoping for – he could hardly have left me to the mercy of the elements after a conversation like that, could he? So we went back to his oasis of strangeness in the midst of German suburbia. I rustled up some vegetarian fare from his cupboards, enjoying the trust and the marijuana of this unusual and likeable guy.

We headed off in the early morning, making ridiculously good time in his rather superior vehicle and not talking so much, content to follow our own respective thoughts to the background of fast-diminishing countryside and the psychedelic sounds of the Asian Underground; chants, tablas and sitars of ancient Indian ragas blending with the samples, drum patterns and effects of synthesizers invented within the last decade or so.

We arrived in Vienna in the mid-afternoon. I left Jan with my copy of Kahil Gibran’s “The Prophet”. He gave me the Asian Underground tape, 60 schillings and of course, his E-mail address.

So I found myself wandering the streets of Vienna, again. It’s a very cool and detached town, whose populace give new meaning to the word ‘bourgeois’. They drift through long, cold winters and pleasant summers, posing and pouting but never really leaving second gear.

The nature of the people finds it’s reflection in the Viennese architecture that draw huge amounts of tourism in the summers. Enormous cathedrals and stately buildings dominate the scene and the style is characterised by sharp, angular relief-work. It mirrors the scornful expressions of the women of the city as they make their way below past the opulent cake shops.

I hopped on what must be the smallest underground train system in the world and as such is a monument to the languid take-it-as-it-comes attitude of the Viennese. As is the case in much of Europe it’s no problem to ride without a ticket. There are no machines or officials to routinely check that you’ve paid as you enter-you just have to deal with the occasional hazard of the obnoxious ticket police who shunt around the network all day, (dressed as hippies or businessmen) making sudden, aggressive raids on the carriages.

This arrangement suited my friends who lived here. Okay, it was no fun but they simply took it as their due that every now and then they would be caught and shouted out by these fascistic minor officials with walkie-talkies who then fined them lots of schillings. It worked out cheaper in the long-run than buying a ticket every day and why walk when you can ride? Easy for me, of course, as I just needed to flubber around in confused and apologetic English and they’d eventually get frustrated and leave me alone, perhaps with my false address written down in their notebooks.

I stepped out into the Jewish quarter of town by the sullen canal and passed various kosher food stores, between which strode Hassidic Jewish men in black suits, caps and long beards, with earnest and purposeful expressions, doubtlessly wrestling with some Biblical contradiction that was teasing their minds. Police could be seen hanging around to offer the synagogues a constant protective presence against the legacy of persecution that has seemed to follow them wherever and whenever for the last five thousand years.

I climbed the steps of the apartment building, ignoring the elevator and rang the bell of the friends I was hoping to stay with. They were pretty surprised to see me-a little freaked would be closer to the truth. The first question they asked me with nervous and fearful eyes was:

“How long are you going to stay?”

Having met two of them first in Goa, I’d already taken up their ill-considered invitation to come and visit in the May of that year and had managed to pretty successfully outstay my welcome-to which there is something of an art.

*

They were four girls living in the flat and they all possessed minds of sharp and destructive honesty that reduced any insincerity to dust. O beware, innocent and vulnerable wayfarer! These were women to reckon with and woe become anyone caught in vain or narcissistic speech- four more earnest and acute souls you could not hope to find and they hunted down with a vengeance any signs of pandering to the ego. The result was that they gave themselves (and everyone else) as hard a time as their strength could bare.

But for all their tough exterior their debates often centred around the eternal issue of whether there was any such thing as true love, sides being chosen on the basis of recent experience. We’d eventually muddled together some kind of living pattern and, after the initial annoyance and incomprehension, they found my sideline presence amusing:

“You just sit around all day doing nothing!” They cried. Which was not true. I wrote at least one song every few days and I rarely missed my morning session of yoga. I considered myself an island of peace amidst the helter-skelter emotional melodrama of their day-to-day lives.

They had effectively watched me starve in the two weeks that I’d stayed with them. I had sat around almost empty-handed in a fiercely competitive and possessive kitchen where they wrote their names on their bottles of soya sauce and jars of honey, lest their supplies be usurped by one of the others. To be fair, they had shown me some ways of making money, including the racket of picking up 5 schillings per empty bottle left behind at the local alternative nightclub-but I had rejected this as sleazy. So, with occasional lapses of charity, they ate huge meals before me while I attempted to survive on three bowls of porridge and a kiwi every day.

But then after a hungry week of chewing oats, I spied a poster on the tunnels of the underground advertising that the dance and rhythm performance extraordinaire, “Stomp”, would be playing the next day. With a smile like the Cheshire Cat, I remembered that the sound engineer of the show was a friend of mine from Brighton.

“Tom! What are you doing in Vienna?” My friend, Mike, asked me in amazement.

“Starving, mainly.” I informed him.

I came down the next night, watched the stunning show from a choice seat and was afterwards taken along to the opening night party-where were gathered all the top socialites, personages and paparazzi of Vienna, showing off their new clothes and making small talk. I headed straight for the buffet where on a pristine scarlet red cloth, covering the tables that ran across three sides of the room, was laid a spread of at least a hundred dishes. I piled my plate with the smoked salmon, the olives, the mango, the chocolate gateaux and the French cheese. Upon returning to the free bar to claim gratis beer and wine, Mike took a photograph of me leaning against the counter, with my absurdly-filled plate in one hand and a glass of Bordeaux in the other-the spoken caption was:

“Tom joins the bourgeoisie.”

After boozing with the crew of Stomp, whose capacity for making rhythms out of anything from newspapers to lighters, was matched only by their ability to consume incredible amounts of alcohol and other such stuff. I stumbled back home, leaving their little bubble of London-streetwise on-the-case accents behind me. On the way, I had fancied a little more excitement in my inebriated state and stumbled into an open-air nightclub. Seeking a good place to piss, I walked through to the darker parts of the beer gardens. I saw a choice looking spot by a tree, just across a black shiny path. Two moments later, I discovered that it was not a black shiny path.

“Hmm, ” I thought, “Someone’s walking in the pond. It’s me.”

*

That was May and a lot of water had passed under the bridge since then, without me falling into it. Now August heat soaked all of Europe and left sultry evenings in the wake of the sweaty days. I walked down by the canal where the sunset lay on the silent drift and crossed the town to visit Meriana: a Bulgarian lady who had just secured Austrian citizenship with her marriage that day. She’s a bubbly, bouncy girl with flames licking about her. We had first met on a Goan dance floor where our mutually exuberant kinetics found affinity and she had recognised me on my last visit to Vienna by virtue of my twirling arms in the darkness of the Flex nightclub.

She was a true Punetic-a regular character of the Osho Ashram in Pune in West India. She was a perfect fit for the archetypal model of wild and creative promiscuity in incessant and hot pursuit of sensual realms of passion. Her eyes twinkled with feline mischief and her rampant demeanour meant that she had trouble to even sit at the dinner table for more than five minutes before something else would snatch her attention.

She spent half the evening on the telephone listening with guilty unease to the sobbings of a guy who’d fallen in love with her and was now realising that she was an eternal free agent of the night. We’ve never gotten involved and I seriously doubt if I could keep up with her 100 kmph pace-but we had a strange and touching supper together and at the end of it, she booned me 500 schillings to “spread good vibes with.”

The following morning, before I left for Hungary, I walked up to her apartment and left a note outside her front door. It read:

“Meriana, you are beautiful.”

Chapter 3

Bound for Budapest (Hungary)

“Let there be wine, women, mirth and laughter, Sermons and soda water the day after”

(From “Don Juan” by Lord Byron)

As usual, it was a complete bitch attempting to hitch out of Vienna, as traffic-jammed streets seemed to merge into snarling motorways without any graceful interlude. It was hot and Western Europe seemed reluctant to let me go. But I couldn’t return to the mocking laughter of those Austrian females who were both impressed and skeptical as to my voyaging ambitions:

“I hope you don’t get killed!” They had sung as I left their apartment.

I sang songs to myself and tried to prevent any curses for the passing cars from surfacing, as I always feel you then enter on a downward spiral. According to the Zen school of hitchhiking, if you swear at a car after it fails to stop for you, then you’ve also sworn at it before it stops for you-and what driver is going to help someone who’s hurling abuse at him. But sometimes…

“Fucking bourgeois self-centred middle-class mundane shits!” I yelled, with a headache coming on from the heat. Almost immediately however, someone pulled over and took me out of town to a lazy, hazy hill where I sat on my bags and stared out across a sweeping silence of wheat fields and cottages.

One hour later, I was in a van with two Germans who were off to see the Hungarian Grand Prix. The border was straight-forward and I waited eagerly to see what changes the ex-communist lands would bring. The Germans swapped bundles of schillings for even larger amounts of Hungarian Forint at the Bureau de Change. The single note that I took to the counter seemed rather paltry in comparison-but it all counts, no? As long as I can buy my raw beef stroganoff and pilsner beer at the end of day.

I had an address for a girl I’d never met before who lived a little way outside the capital. I dreamed of some provincial romance with an autumn-haired Balkan beauty; gathering fresh eggs in the morning from the unlikely laying places of the hopelessly errant chickens; long evenings playing with the spriteful children of the sprawling village family, three cats and two dogs in the yard-something smells good in mama’s cook pot! And look! Young Jan is whittling away psychotically at the foundations of the house, whilst I and my love lounge around on an old wooden swing in the soft summer twilight. Ah.

Concrete. Big fuck-off lumps of concrete posing as places of human residence, rising from the towns that we passed en route to Budapest. Okay, I’m not the first person to notice that the communists didn’t win any prizes for architecture but they actually seemed proud of these grey monstrosities-symbolic constructions of proletariat sweat, I guess. The high-rises stood like some irreverent moon at the gods and I wondered if they were meant to choke the colour out of the world. They succeeded.

Our visions extend as far as the nearest horizon but for those living in the cities of Eastern Europe, the next concrete high-rise was about as far as their eye could take them. Where could the dreams and inspiration of a William Blake-visionary arise in Hungary? Communist philosophy seems to have precious little time for anyone who sees any end other than the glory of the Common Good. Try getting the word metaphysics out of your mouth before a sneering Lenin-like laugh cuts you short. Anyone for a military polka march? It’s sure that they’d have shot the birds who sing in the morning too, if they could have afforded the bullets.

Budapest was big and bustling and I jumped out of the van to start walking purposefully in no particular direction at all, in the same kind of bleary haze that accompanies most people in the early morning hours. The signs of frontier Western commerce were evident with flashing neon Kentucky Fried Chicken signs and suchlike-but they lacked the almost regal status they command in the shopping centres of the West. Here they seemed almost pitiful token symbols in the obscurity of these grey lanes, like an ambassador who’s been in the sticks for too long. Outside the supermarkets sat darker-skinned women and men, selling apples and peaches from their portable set-up stands, reminding me of Asia.

It was getting towards dark and I wasted half an hour hesitating between stepping onto the stage for an unlikely romance in the nearby village or heading on East. Somehow it was hard to maintain the dreams of rural love in the congestion of Budapest. I let my shyness get the better of me and hustled my way out onto the highway.

I had intended to stay and dig Budapest but the horse-trap 19th century cultural capital of my imaginings disappeared in the smog of the late 20th century reality. Big cities are not always such great places for the ragged traveller who has no way to pay for a hotel room-yeah, avenues can open up if you find the right kind of scene where musicians and dope-smokers hang around. But in an unknown metropolis, it’s just as likely that you’ll walk into the wrong part of town, where the twilight is not so pleasant. Naive and tired hitchhikers who don’t speak the local lingo can meet with heavy situations if they turn the wrong corner.

With more luck than usual, I managed to find the right place to stand and a car skidded to a halt within minutes, even though it was now dark. My driver was headed to Debrecen, which was near the Romanian border and so I sat tight and made polite conversation. He was a young, self-employed guy with his own business and he drove fast, intent on reaching his hometown where his girlfriend was waiting for him before she could fall asleep. He seemed pretty impressed with my resolve to get to India and I allowed his spoken compliments to my bravery to fill the gaps inside where my courage ought to have been.

Man, I wasn’t even sure if the route was possible; I didn’t know if anyone would feed me and I half-expected to be ambushed and beaten up by a bunch of gypsies, they’d rob me of my clarinet, my good looks and my passport containing all the visas I’d painstakingly obtained-making it impossible for me to make the overland route-Courage? Come on! Foolish? Maybe. Naive? Most definitely. But God is supposed to love drunkards and fools and I counted myself as one of the favoured.

As I was sort of hoping that this nice young guy might give me a bed for the night at his Debrecen home, I accepted his offer to recline my seat so that I could sleep, hoping that my apparent fatigue might evoke his charity. As we came near his town, he switched on the radio to wake me up and he pulled over by a garage-no warm bed was awaiting me but he did give me a handful of coins. At my gratitude said:

“Wait, I have paper also.” Which seemed to sum up the whole money thing-these green and blue survival tickets that won’t keep you warm and certainly don’t taste good. He was more than generous and now, after leaving England with nothing my fortune had swelled to around $80, largely thanks to the kindness of strangers.

I wasn’t going to spend any of that on a place to stay, of course-I mean, what kind of self-respecting freak am I? Money is a thing reserved for the tasty cakes in the windows, the spare parts for my instruments and the drinks at the bar to win the hearts (and the bodies) of dark and sultry gypsy maidens. Sweet tastes and fun times are the things that keep you going on the road. Nothing will lower your spirits more than standing by the highway for hours with an empty belly. Or staggering through some drizzly town where everyone is supping croissants and coffee behind the windows of warm and friendly cafes where you can’t afford anything on the menu. So, true to my principles, I walked into the garage restaurant and ordered three pieces of cherry strudel and a mint tea.

Europe seemed to be going past quickly as after a week, I had come 1500 miles to the heart of the Continent and fate had been so kind in lining my pockets that I felt almost fraudulent in carrying so much money. Alright, I wasn’t loaded by most people’s standards but for a bread and soya margarine hippy I was doing pretty well. I figured that if the hitching got really bad, I’d at least be able to buy some train tickets further East. Then I’d be obliged to continue the journey by hook or by crook-probably ending up facing the hook, if the legends of traditional Islamic justice bore any truth. I imagined myself being caught pilfering apples from a market-stand: “I’m innocent!” I’d cry-or rather: “I’m English! Doesn’t that count for something?” With hands chopped at the wrist, how would I ever play my clarinet again? (Or indeed thumb a lift?)

Catching myself as I almost fell off my stool in a half-dream, I grabbed the counter for support and drew half-a dozen glares-How much of that had I spoken aloud? Time to leave.

The night was cool and the ground already wet with dew-that moist curse of all outdoor sleepers and the forerunner of creeping tuberculosis and consumption. But there was no way I was going to try to hitch on to Romania that night, as the dark hours are never advisable hours to cross borders, especially in dodgy police-states.

I walked away from the revealing street lamps and strode over an area of redundant wasteland until I found a bush I could sleep behind, out of the view of anyone who might happen to be walking nearby. I laid down my waterproof poncho on the ground as thin insulation and curled up with my passport, cash and clarinet buried at the bottom of my sleeping bag. I settled down to the lullabies of honking trucks 100 yards away but I passed out okay. Sleep is always the time when I feel safest-as I found out to my cost in Prague three months before.

*

I had been led to a little park by a once-beautiful Russian lady, her features now stretched by her smack habit. She assured me we would have the security of her friend who worked as night watchman for the museum there. I slept on a wooden bench whilst she roamed the park in her heroin introversion.

I dreamt of theft and strange, shifting figures. At one point I awoke and saw two young guys walking past, carrying something heavy. When I fully came to at dawn, I realised what that ‘something’ was. My guitar no longer rested against the bench as meal-ticket and friend.

I then had to hitch on with just my wits back to England and went quite hungry along the way. I’d also lost 20,000 words of a novel I’d been writing and some crucial addresses-all of which had all been stashed in the pockets of the guitar-case. Of course, that gave me less to carry and was a good sob-story for my benefactors that day. It also gave me the inspiration to get a new instrument-But no way was I going to lose my jazz blowpipe now.

*

The minute you start to sleep rough in Europe, you step outside the area of accepted social conventions into a shady zone of chance where nice people don’t go. There is nowhere really set aside for those sleeping out: no free public shelters to provide some cover, warmth and safety-the idea presumably being that such a facility would be abused-whatever that means. So when I turn up in an unknown town I have to search around in streets and parks, prospecting the comfort of climbing frames and bushes. How many people do you know who sleep outside each night? Millions of people do, in countries all across the world but most people would rather not know how or why.

Most of society is far too squeamish for that kind of thing and the average person’s survival kit would consist of a collection of visa cards and cheque books. If the crunch ever comes to modern civilisation and all the infrastructures fall apart, then my money is on the hitchhiking types to be foremost among those left standing. These will be the people who know how to make a fire and cook on it; people who won’t wilt at the thought of using water instead of toilet paper. Anyhow, these are the kind of thoughts I end up with to salvage some feelings of pride and self-worth after a cold and lonely bed.

I got through to the morning without being robbed, beaten-up or run-over by a ten-ton truck. I gathered my things and stumbled away into town with the strange injuries in the joints one seems to pick up during the night. Impervious to the funny looks coming my direction from the early-morning commuters, I decided to sit down on a grassy corner and make a breakfast of tinned tuna, bread and garlic. Like a panda eating bamboo, it cost me almost as much calories to open the tin with my fake Swiss Army knife than anything I could possibly have gotten from the contents.

For the next three hours the passing cars slowly turned my mucous membranes black with their exhaust smoke. No rides. It was the road to Romania and from what I’d been told, the two countries didn’t get on too well. Apparently, the Hungarians tend to take a rather superior social and cultural eye to the ‘thieving, hitchhiking, gypsy-cousin Romanians’-and no doubt I looked the part.

But waiting is all part of the deal, nowadays, as the world grows more paranoid and fearful about the unknown. In the old days, hitchhikers could be seen on every main road and it was simply a matter of common good spirit to pick them up and help them along their way. My grandpa used to tell me of the wartime days when young servicemen could be seen by the hundreds by the sides of the roads, trying to get back to their stations after the excesses of their drunken weekend leaves with their family and sweethearts.

He told me that he could always count on drivers to save his neck from the fury of his commanding officer, by going out of their way to get him back on time.

“Don’t worry, son,” They’d say, “We’ll get you back fighting Hitler before dinnertime!”

He’d have had a hard time nowadays, if he had been alive to try it because wearing a uniform or any suspicious outfit is enough to automatically disqualify you as a potential passenger. I learnt this a couple of years ago when it took me and my friend, Tony, two and a half days to hitchhike to Scotland. I was proudly wearing a kilt, sunglasses and a towel wrapped around my neck which wouldn’t fit into my bags. Tony has never quite forgiven me.

No longer is a hitchhiker a helpless stranded soul but rather a likely mugger, rapist or crazed crackpot with a mind as random as his method of travel. Of course, some people do stop-often those who have hitched before themselves. But it becomes harder and harder as the Press feed a never-ending stream of hysteria to the neurotic public. We’re urged to remain behind the safety of a locked and bolted door, opening it only to selected family members and only then if they can provide at least three valid forms of identification.

In England, a single incident of a nasty murder or abduction has the power to change laws affecting the lives of the rest of the 55 million people living there, such is the frenzy that can be whipped up by the unscrupulous mercenaries of the media. And in America, a bloody film entitled “The Hitcher”, hugely regressed the tradition ,as anyone who saw the movie was paralysed with the image of the psychotic repaying the kindness of the driver who stopped for him with savage brutality and violence. It’s your worse nightmare, folks.

I dreamed of the days of the 60’s when VW vans full of marijuana smoke were said to pull over like a shot to rescue anyone flagging a ride, a time when hoboing around was an understood and approved thing to do, if a little eccentric. But as times grow harder and money grows scarce, so too does the general spirit become miserly and suspicious and no one dares risk a dream of romance and adventure-‘We’ve all got bills to pay-why should we pick up some tree-hugging freeloader?’

And so we wait and we wait and we wait. In some countries longer than others. The Germans always pick you up and even the Swiss aren’t immune to a polite request to ride in their car. But try hitching across Spain and make sure you carry a few days worth of food with you – I think they consider us to be lower than the gypsies. France can be a bitch also whereas England can be a breeze if you go from service station to service station. Either way you have to be prepared to wait some days to get across Europe and thus you have to carry your bed with you and expect to receive a fair amount of animosity along the way from your average idiot on the road. They slow down to raise your hopes and then speed off, they shout abuse out of the windows and sometimes even swerve at you.

Despite this, I must admit that I had it pretty good on the road. I was young enough (20) to seem fairly unthreatening and so thin that many people felt I needed a good meal. On top of this, Israelis are always telling me that my name means ‘innocence’ in Hebrew (though ‘naiveté’ might be closer to the truth) and I have the general lost, dreamy manner of someone who really needs to be helped along his way. What else for this brief self portrait-Oh yeah, I’m damn good-looking too!

On this occasion I’d had enough of waiting and didn’t want to die as a pointless martyr to the virtue of Patience. I began walking back to the train station to see if I could get some transport over the border and into the Dracula country of Transylvania. As I strolled, I made a few half-hearted attempts to thumb the oncoming cars and one of them actually pulled over.

A red-faced, grey-haired man opened the passenger door and asked me something in Hungarian (A very strange tongue that I never made the slightest effort to learn). In response, I whipped out my map page and tried to point out to him the name of a town that I couldn’t pronounce.

“Do you speak English?” He asked me in classic stage manner. I threw back a hip and answered with stature and elegance:

“I am English!”

“Well, come on, then!” He replied with a laugh. I climbed in and began chatting easily and quickly with this wild-haired guy who told me he was originally from Poland but had spent the last ten years or so living in Amsterdam.

“Well, how about this then, Tom-An Englishman and a Pole driving an East German car in Hungary!” And of course everything was wonderful, as it always is with the happily-drunk. Though he wasn’t going very far, he invited me for a drink which he bought at the local petrol station. He was friends with the petrol attendant-in fact he seemed to know everyone-and in the general good atmosphere it was decided that I should stay and rest for a day or two, share stories and of course, get very drunk on the excellent Hungarian beer.

Naturally, my new Polish friend, Bishek, had to hide his can between his knees whilst driving and I accompanied him on the rest of his morning’s work, as he delivered spare engine parts to the shops in the area. Our adventures included an episode taking a stray dog to the vet. Bishek frightened the sensibilities of all the respectable cat owners with our ‘illegal’ rogue mongrel. A dog without papers, he had dark grey hair that was as unruly as his character and he bounced alongside Bishek in the happy knowledge that he had an ally. As I died of fatigue in the sun-baked car, a quick glance back at my approaching friends could not tell the difference between the pair.

Ah yes, it was all good laughs and jokes until that is, we reached home where his girlfriend was waiting in absorbed melancholy. Bishek whispered to me that she had only discovered a few days before that she was pregnant.

Our raucous cackles fell flat as chapattis on the silent atmosphere of the apartment and I immediately got the feeling that my timing as wandering guest was not so good. But Zsoka, as she was called, did her best to mask the fact that she had been crying for much of the morning and began to prepare a lunch that I dared not refuse-though it was the first meat I had eaten in three years. Now on holiday for the weekend, Bishek tried to gloss over the awkwardness by sloshing more and more ‘brown water’ and soon began to dominate the conversation with anecdotes from his time in Nepal-which were interesting from what sense I could make of them.

He had been walking near his flat in Amsterdam, when he ran across a German girl he knew, called Lotti. She was involved in the Tibetan resistance movement and was someone, Bishek told us, who had ‘gods with her’. “Hey Bishek!” She had called, “Do you want to come to Tibet to make a documentary program about the injustices there?” Three days later they were all on a plane to Nepal, due to sneak into Tibet without visas or permission. Bishek was scouting ahead to make arrangements in the next villages, joyfully throwing back the local booze whilst everyone else was crippled with altitude-sickness.

“You bastard!” Lotti had growled at him.

The expedition failed but the drama wasn’t about to stop for my friend, because back in Kathmandu he’d seen a young Tibetan guy being beaten and kicked on the ground by a bunch of Nepalese police.

“Stop! Stop! I’m a doctor!” He had cried, the soldiers parting to let this wild grey-haired lunatic through.

“This man must go to hospital now!” He shouted with authoritative madness and then bundled the youth into a taxi and escaped, leaving behind a very confused gaggle of officers who had the growing feeling that the joke may have been on them. After that, Bishek told us, he couldn’t pay for anything in the town again as he was plied with food and drink wherever he went, the many Tibetan friends and relatives of the boy insisting on repaying him for his brave deed. I gratefully accepted the invitation to sleep and was given a cool double-bed in a large and shady room-Maybe now they’d have the opportunity to talk. Though Bishek seemed to have sabotaged the chance for dialogue with his speedy inebriation. I felt for Zsoka, as sometimes a flurry of drunken laughter and smiles just won’t do.

I woke again in the late afternoon. Bishek was out so I took the opportunity to get talking to Zsoka. She turned out to be a delightful and intelligent woman, who struggled daily with the alcoholic passions of her boyfriend.

She was midway through describing the beautiful towns and countryside of Hungary when Bishek burst in wild and incoherent as a Dean Moriarty, declaring that I had to come with him at once. He was so plastered and excited that it took a while for me to realise that there was a taxi waiting for us in the street. I felt bad for the embarrassment and hurt that this was visibly causing Zsoka but I was a guest in the hands of my host and so I allowed myself to be pulled away, though I acted like a moral drag on Bishek for the rest of the evening.

We went down to the Jazz Cafe and a cool bunch of people was gathered in this bohemian hang-out spot where artists and musicians sat at long tables beneath poster portraits of Charlie Parker, John Coltrane and Miles Davis, hanging from the walls that glowed purple and orange in the light of the mounted side lamps. Bishek would not let me pay for any drinks and seemed almost offended at the suggestion. However he was generally uplifted by our meeting.

“Ah, Tom! With you, I am travelling once again, you know? In my mind!” He confided, in between spells of introducing himself (and me) to every pretty girl in the club. Several times I had to prevent him from making ostentatious showman announcements that the whole cafe must stop to hear me playing the harmonica. Hard work, actually.

But for all of the guilty role that he wrote for himself at home, Bishek was a bold and generous guy, possessed of more spirit and zest for life than ten people wagging their fingers put together. I like to dig people for their qualities and relax about their failings; I end up sympathizing with Jerry Garcia, when he sang:

“I’ll set out running but I’ll take my time A friend of the devil is a friend of mine”

It was getting late and I was trying to cajole and blackmail Bishek into leaving-a near impossible task-when I found my efforts impeded by the compulsion to talk to a pretty and petite woman who had been with us at the table and who now stood in front of me by the exit.

“I will be here tomorrow, too.” She told me and that seemed to be a fairly clear hint. Her name was Marianne and she was visiting Debrecen for the weekend, due to return to Budapest on the Monday. Through my drunken stupor, I tried to gather the implications of this. I promised to meet her the next evening.

I pulled Bishek into a taxi and we came back to a dark apartment. I quickly excused myself to lay down for bed. For the next hour I heard shouts and tears that would have served for an anti-alcohol advertisement, as the ‘demon of liquor’ spread its strife in age-old style.

The next morning, whilst Bishek slept soundly, I attended a classical music concert with Zsoka. We were overwhelmed with the intricate beauty of the flute performances of two young girls. The first was the less proficient and more nervous but somehow more charming for the anxious modesty with which she played. Zsoka took me for lunch and we ate real Hungarian salads and soups, strange and salty-a clear sign that the ‘cook was in love’, according to my hostess.

In her, I saw some of the less celebrated aspects of the heart: in the patience she exerted in her domestic struggle and I learnt something about inner strength. She spoke softly and it was touching how automatically she had accepted me as witness to their drama, I, a passing wayfarer that her husband had brought home with a ‘look what I found’ merriness.

“He has changed, Tom-when I first met him five years ago, he was much worse! But now I’m thinking that maybe it is not enough change after all this time.” When we returned, she and the hung-over Bishek, just out of bed, went on a bicycle ride to the country and left me alone in the flat.

I spent all day sitting around, playing clarinet, reading the odd English book that was lying around and thinking about my evening rendezvous with Marianne. The day grew older and older until I watched the sun sink, its dying rays feeding the flowers and window-boxes that adorned the exterior of the tower blocks-their one saving grace.

Bishek and Zsoka did not return until dark, after 9pm. It seemed as though things were more settled between them but it had obviously been a heavy day. It seemed an inappropriate time to suggest going out to the jazz club.

Early the next day, Bishek woke me to join him making deliveries on his Monday morning shift. He would put me on the bus for Romania at 10am and I’d resigned myself to forgetting about my dark haired beauty from Budapest. But then as we stopped for petrol at the local service station, we met our friend, Janski, who worked there. He told me that Marianne had waited sadly for me all night and was now pissed off. He gave me her phone number and bade me call her.

Bishek at once grasped that I had stood her up in sympathy to the events of the previous day and went out of his way to arrange a meeting with Marianne for me, though he counseled caution:

“Ah, Tom, maybe you should get to Romania if you want to reach India, after all, Budapest is West from here.”

“But Bishek, those brown eyes!”

“Ha, ha-Beware the eyes of Hungarian women, I can tell you! But I don’t know how to advise you here.”

After a morning and an afternoon of several false starts, missed phone calls and train deadlines that existed in our misinformed-informed imagination, Bishek finally got to speak to Marianne herself on the phone. At 3:30pm, we pulled up at the rendezvous by a famous statue. She was already waiting and gave us a nervous wave as we drifted past to find a parking spot. She was far more shapely than my drunken recollections and whilst Bishek discreetly hung back to attend a non-existent engine problem, it took just two minutes conversation to settle that I was going with her to Budapest on the 4:30 train. She ran to collect her bags from her mother’s apartment upstairs and didn’t quite understand the immediate reluctance of Bishek or I to come with her. She disappeared to grab her luggage and my comrade and I agreed with schoolboy humour:

“Always avoid the mother!” We laughed.

Bishek made me promise to let him know what happened in the ‘next part of the story’, as we’d been referring to the day as a strange comic drama in which we were the dizzy protagonists. We parted with a wink, a laugh and an unspoken bond of mischief between us.

*

Enjoying the book? Sign up above to get the full book as a PDF or if you want to support the author, buy a copy!