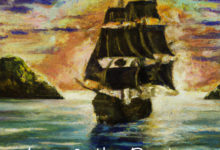

“Clowning is an outpouring of love.” Schmuel says and the moistness of his round, dark eyes accompany the sentiment. His spine straight, he sits with gentle dignity and rarely looks at us directly, seeming to address the fireplace more than anyone else. There’s an unreachable detachment about him.

I was 21 and had ideas about becoming a clown. Staying with a friend in the Galilee, Frieda had taken me to meet Schmuel that morning to see if he might offer some words of advice. We found him outside the carpentry with a broom in his strong hands, sweeping flecks of Zen to the side.

With almost archaic etiquette he declined to address me directly, putting all questions through Frieda while I stood at the side. Finally he turned to me and said:

“So you’ve come all the way from England to Israel to become a clown? Well that shows you’re pretty silly and that’s a good start.”

As promised, he’s shown up at Frieda’s house this evening and the three of us sit on cushions by the fireplace drinking tea. Schmuel thought that this might make an Englishman relax and make it easier for us to communicate.

Schmuel seems a little weary when we ask him to recount his life as a clown. It’s as though it’s a struggle to connect with us. As he gets into the flow of his talk, however, bright memories flash through him and he cannot help but make us laugh.

“Get yourself a red nose, a silly hat and big shoes,” he says “And go stand in the market in Tel Aviv. Stand there and give out flowers to girls who pass. Or else become the village idiot. Stand there witout moving until you begin to weep and drool at the mouth.

“Do whatever is comfortable. Explore posibilities. And be patient. To clown to an audience is to apreciate an awareness of energies.”

Schmuel smiles and his few remaining yellow teeth make an appearance. He tells of us his experiences of clowning to groups of children. When they would insist on jumping into the act, Schmuel would give them a red nose to wear and make them his little helper.

“It was then I realised that as a clown I was not playing against my audience but rather playing with them. Performing to children helped me to abandon my aims and instead just create from the moment.”

Listening to him speak all kinds of possibilities begin to sprout in my mind. He encourages me to just step out and let the street be my teacher.

But though he makes us laugh, he speaks of all this fooling as something that has settled in his past. My curiousity stirs his imagination for a few moments but then he gives a poignant smile and says:

“Ah, here we are! You at the start of your clowning career and me at the end of mine!”

He look like he’s ready to leave and I’m conscious he’s honoured us by giving so much of himself these past two hours. But then he pauses and tells us:

“Everything the clown does is for his Beloved – even if that’s a dog whose nose you kiss. It may be that you have the interest and attention of no one on the street except a three year-old little girl. So you take her hand and start to walk off don the road to Infinity – see how far you get before the mother stops you…

But in all you do, do it for your Beloved.”

Then Schmuel becomes a little grave, perhaps having opened up more than he’d intended. With barely a word he bids us a discreet farewell.

Perhaps the image of the weeping clown has become a cliché. But in Schmuel, who I knew for just one evening, I saw a man who could not help but percieve both sides of the heart. Where the tragic is married with the absurd and comic.

A clown tests our limits. By stepping outside of conventions and assumptions, he encourages us to do the same.

And this is how I remember Schmuel.